But every digital workflow begins with managing the files we put on our computers. The workflow you choose will depend on your proclivities as a researcher and the kinds of materials you use. Just as there is no single perfect, catch-all research method, there is no single “right” digital workflow. In the end, every good digital workflow ultimately comes down to two activities historians have long engaged in: managing our files, and organizing our citations. While the forms this work takes might be new, the principles that guide their organization are as old as the index card.

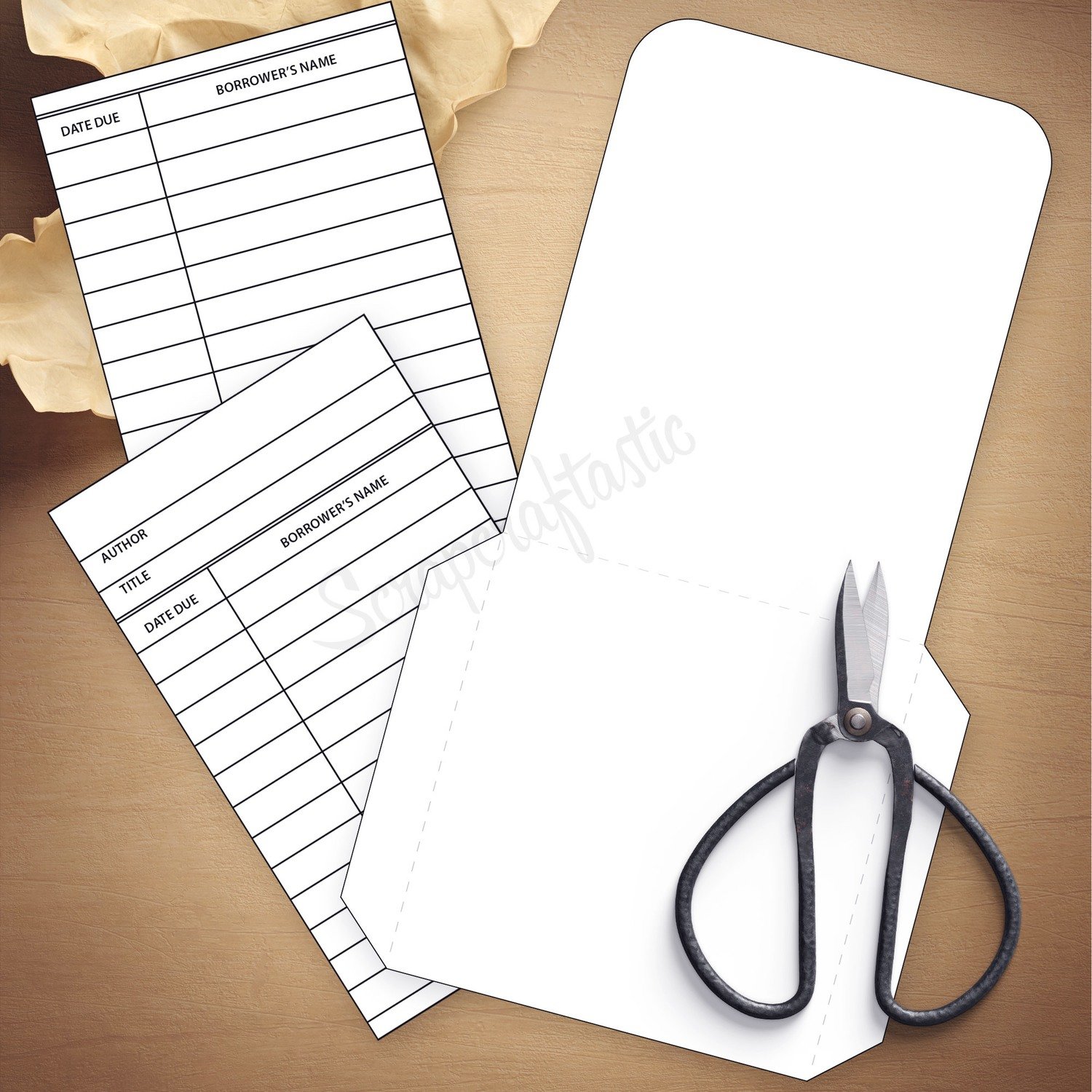

FILE CARDS FOR FILES SOFTWARE

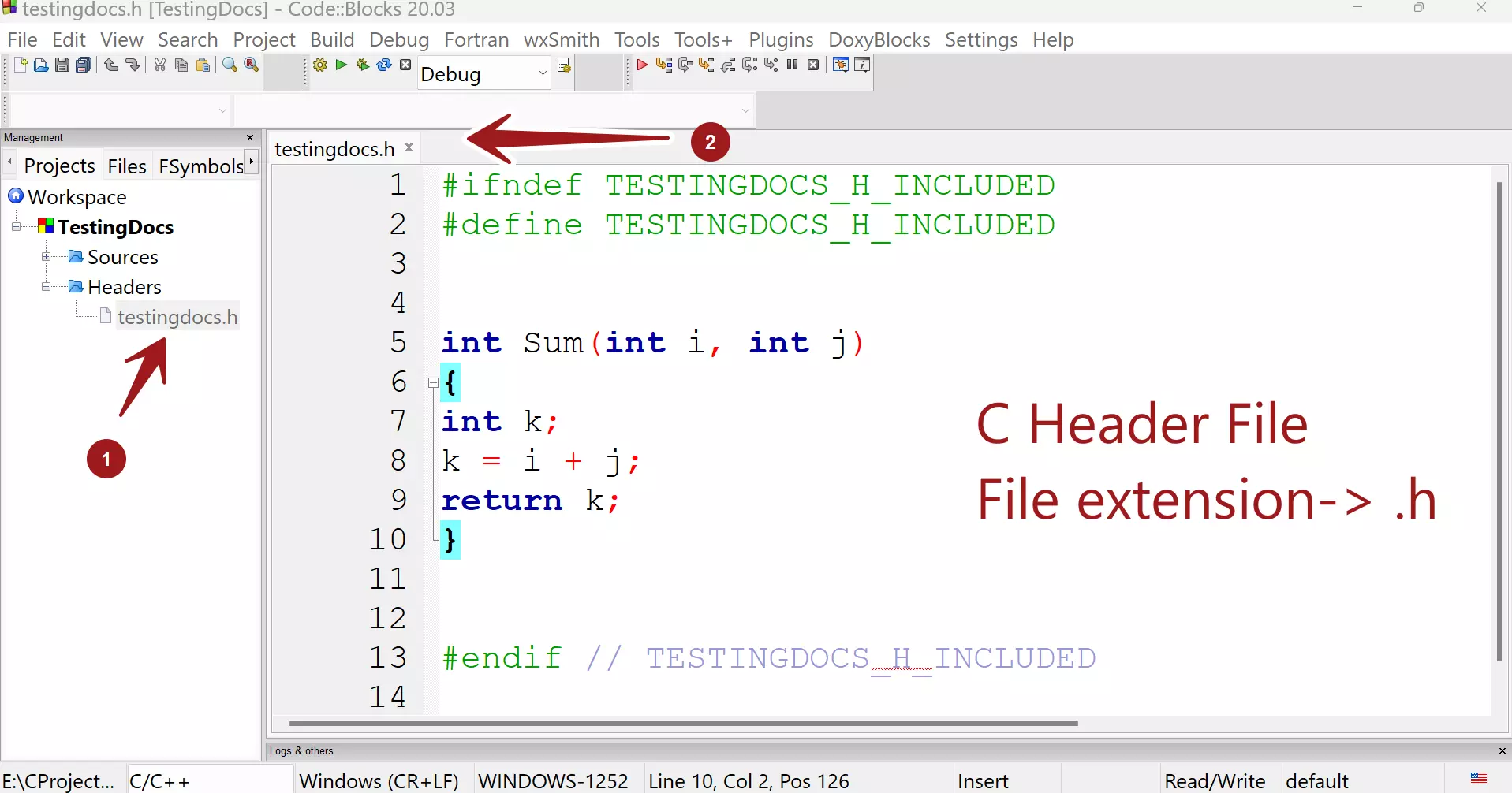

Databases and asset-management systems can help store the digital content historians now acquire, while bibliographic software can connect that material with our writing and research. While such a process on its face might seem as bewildering as the proliferation of primary sources themselves, there are thankfully a number of tools and tactics that can facilitate the organization of our increasingly digital research archives. Given this deluge of digital primary sources, it is incumbent upon today’s historians to establish a digital workflow that manages it all.

FILE CARDS FOR FILES DOWNLOAD

The change in the types of materials historians use has also been accompanied with an increased scale of abundance, as a single scholar can now download in an afternoon what some scholars acquired in a lifetime.

Notecards, photocopies, and microfilms have been largely replaced by PDFs, jpegs, and searchable databases. While scholars once primarily trafficked in material objects, historians now work with a great deal of digital material. But his preferred method for organizing his research has undergone a revolution in the last decade. So much of the advice this generous historian gave me turned out to be right. “Make sure you organize your cards early,” he advised, proudly thumbing through thirty years’ worth of 3” x 5” notecards.

It soon became clear, however, that he was referencing the index-card cabinets that sat on his shelf.

When the conversation turned to research, this established scholar pointed to his bookshelf and pronounced, “One day you too will have these things filling your shelves.” At first I thought he was talking about a row of published work. One historian in particular was very generous with his time, talking with me in his office for over an hour about writing, teaching, and the academy. As a newcomer, I was eager to heed any advice these senior scholars might offer. One of the first things I did when I started graduate school in 2003 was to contact a number of established historians whose work I admired. From Index Cards to Text Files: Digital Workflows for Today’s Historian Chris D.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)